Next: 13.4 Discussion and Exercises Up: 13. Data Structures for Previous: 13.2 XFastTrie: Searching in Contents

The XFastTrie is a big improvement over the BinaryTrie in terms of

query time--some would even call it an exponential improvement--but

the

![]() and

and

![]() operations are still not terribly fast.

Furthermore, the space usage,

operations are still not terribly fast.

Furthermore, the space usage,

![]() , is higher than the

other SSet implementation in this book, which all use

, is higher than the

other SSet implementation in this book, which all use

![]() space.

These two problems are related; if

space.

These two problems are related; if

![]()

![]() operations build a

structure of size

operations build a

structure of size

![]() then the

then the

![]() operation requires on

the order of

operation requires on

the order of

![]() time (and space) per operation.

time (and space) per operation.

The YFastTrie data structure simultaneously addresses both the space

and speed issues of XFastTries. A YFastTrie uses an XFastTrie,

![]() , but only stores

, but only stores

![]() values in

values in

![]() . In this way,

the total space used by

. In this way,

the total space used by

![]() is only

is only

![]() . Furthermore, only one

out of every

. Furthermore, only one

out of every

![]()

![]() or

or

![]() operations in the YFastTrie

results in an

operations in the YFastTrie

results in an

![]() or

or

![]() operation in

operation in

![]() . By doing this,

the average cost incurred by calls to

. By doing this,

the average cost incurred by calls to

![]() 's

's

![]() and

and

![]() operations is only constant.

operations is only constant.

The obvious question becomes: If

![]() only stores

only stores

![]() /

/

![]() elements,

where do the remaining

elements,

where do the remaining

![]() elements go? These elements go

into secondary structures, in this case an extended version of

treaps (Section 7.2). There are roughly

elements go? These elements go

into secondary structures, in this case an extended version of

treaps (Section 7.2). There are roughly

![]() /

/

![]() of these secondary

structures so, on average, each of them stores

of these secondary

structures so, on average, each of them stores

![]() items. Treaps

support logarithmic time SSet operations, so the operations on these

treaps will run in

items. Treaps

support logarithmic time SSet operations, so the operations on these

treaps will run in

![]() time, as required.

time, as required.

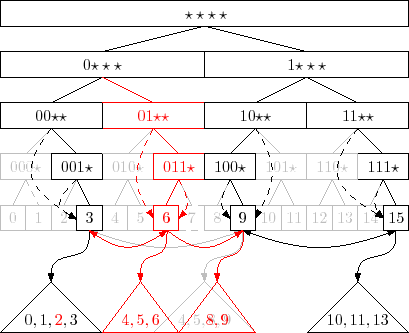

More concretely, a YFastTrie contains an XFastTrie,

![]() ,

that contains a random sample of the data, where each element

appears in the sample independently with probability

,

that contains a random sample of the data, where each element

appears in the sample independently with probability

![]() .

For convenience, the value

.

For convenience, the value

![]() , is always contained in

, is always contained in

![]() .

Let

.

Let

![]() denote the elements stored in

denote the elements stored in

![]() .

Associated with each element,

.

Associated with each element,

![]() , is a treap,

, is a treap,

![]() , that stores

all values in the range

, that stores

all values in the range

![]() . This is illustrated

in Figure 13.7.

. This is illustrated

in Figure 13.7.

The

![]() operation in a YFastTrie is fairly easy. We search

for

operation in a YFastTrie is fairly easy. We search

for

![]() in

in

![]() and find some value

and find some value

![]() associated with the

treap

associated with the

treap

![]() . When then use the treap

. When then use the treap

![]() method on

method on

![]() to answer the query. The entire method is a one-liner:

to answer the query. The entire method is a one-liner:

T find(T x) {

return xft.find(new Pair<T>(it.intValue(x))).t.find(x);

}

The first

Adding an element to a YFastTrie is also fairly simple--most of

the time. The

![]() method calls

method calls

![]() to locate the treap,

to locate the treap,

![]() , into which

, into which

![]() should be inserted. It then calls

should be inserted. It then calls

![]() to

add

to

add

![]() to

to

![]() . At this point, it tosses a biased coin, that comes

up heads with probability

. At this point, it tosses a biased coin, that comes

up heads with probability

![]() . If this coin comes up heads,

. If this coin comes up heads,

![]() will be added to

will be added to

![]() .

.

This is where things get a little more complicated. When

![]() is added to

is added to

![]() , the treap

, the treap

![]() needs to be split into two treaps

needs to be split into two treaps

![]() and

and

![]() .

The treap

.

The treap

![]() contains all the values less than or equal to

contains all the values less than or equal to

![]() ;

;

![]() is the original treap,

is the original treap,

![]() , with the elements of

, with the elements of

![]() removed.

Once this is done we add the pair

removed.

Once this is done we add the pair

![]() to

to

![]() . Figure 13.8

shows an example.

. Figure 13.8

shows an example.

boolean add(T x) {

int ix = it.intValue(x);

STreap<T> t = xft.find(new Pair<T>(ix)).t;

if (t.add(x)) {

n++;

if (rand.nextInt(w) == 0) {

STreap<T> t1 = t.split(x);

xft.add(new Pair<T>(ix, t1));

}

return true;

}

return false;

}

|

The

![]() method just undoes the work performed by

method just undoes the work performed by

![]() .

We use

.

We use

![]() to find the leaf,

to find the leaf,

![]() , in

, in

![]() that contains the answer

to

that contains the answer

to

![]() . From

. From

![]() , we get the treap,

, we get the treap,

![]() , containing

, containing

![]() and remove

and remove

![]() from

from

![]() . If

. If

![]() was also stored in

was also stored in

![]() (and

(and

![]() is not equal to

is not equal to

![]() ) then we remove

) then we remove

![]() from

from

![]() and add the

elements from

and add the

elements from

![]() 's treap to the treap,

's treap to the treap,

![]() , that is stored by

, that is stored by

![]() 's

successor in the linked list. This is illustrated in

Figure 13.9.

's

successor in the linked list. This is illustrated in

Figure 13.9.

boolean remove(T x) {

int ix = it.intValue(x);

Node<T> u = xft.findNode(ix);

boolean ret = u.x.t.remove(x);

if (ret) n--;

if (u.x.x == ix && ix != 0xffffffff) {

STreap<T> t2 = u.child[1].x.t;

t2.absorb(u.x.t);

xft.remove(u.x);

}

return ret;

}

Finding the node

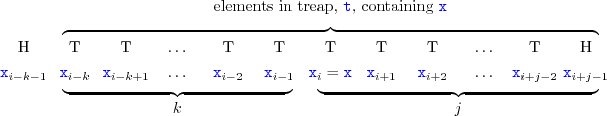

Earlier in the discussion, we put off arguing about the sizes of treaps in this structure until later. Before finishing we prove the result we need.

Similarly, the elements of

![]() smaller than

smaller than

![]() are

are

![]() where all these

where all these ![]() coin tosses come up

tails and the coin toss for

coin tosses come up

tails and the coin toss for

![]() comes up heads. Therefore,

comes up heads. Therefore,

![]() , since this is the same coin tossing experiment considered

previously, but in which the last toss doesn't count. In summary,

, since this is the same coin tossing experiment considered

previously, but in which the last toss doesn't count. In summary,

![]() , so

, so

|

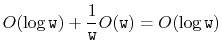

Lemma 13.1 was the last piece in the proof of the following theorem, which summarizes the performance of the YFastTrie:

The

![]() term in the space requirement comes from the fact that

term in the space requirement comes from the fact that

![]() always

stores the value

always

stores the value

![]() . The implementation could be modified (at the

expense of adding some extra cases to the code) so that it is unnecessary

to store this value. In this case, the space requirement in the theorem

becomes

. The implementation could be modified (at the

expense of adding some extra cases to the code) so that it is unnecessary

to store this value. In this case, the space requirement in the theorem

becomes

![]() .

.