Next: 1.2 Mathematical Background Up: 1. Introduction Previous: 1. Introduction Contents

In discussing data structures, it is important to understand the difference between a data structure's interface and its implementation. An interface describes what a data structure does, while an implementation describes how the data structure does it.

An interface, sometimes also called an abstract data type, defines the set of operations supported by a data structure and the semantics, or meaning, of those operations. An interface tells us nothing about how the data structure implements these operations, it only provides the list of supported operations along with specifications about what types of arguments each operation accepts and the value returned by each operation.

A data structure implementation on the other hand, includes the

internal representation of the data structure as well as the definitions

of the algorithms that implement the operations supported by the data

structure. Thus, there can be many implementations of a single interface.

For example, in Chapter 2, we will see implementations of the

![]() interface using arrays and in Chapter 3 we will

see implementations of the

interface using arrays and in Chapter 3 we will

see implementations of the

![]() interface using pointer-based data

structures. Each implements the same interface,

interface using pointer-based data

structures. Each implements the same interface,

![]() ,

but in different ways.

,

but in different ways.

The

![]() interface represents a collection of elements to which we

can add elements and remove the next element. More precisely, the operations

supported by the

interface represents a collection of elements to which we

can add elements and remove the next element. More precisely, the operations

supported by the

![]() interface are

interface are

A FIFO (first-in-first-out)

![]() removes items in the same

order they were added, much in the same way a queue (or line-up) works

when checking out at a cash register in a grocery store.

removes items in the same

order they were added, much in the same way a queue (or line-up) works

when checking out at a cash register in a grocery store.

A priority

![]() always removes the smallest element from

the

always removes the smallest element from

the

![]() , breaking ties arbitrarily. This is similar to the way

many airlines manage upgrades to the business class on their flights.

When a business-class seat becomes available it is given to the most

important customer waiting on an upgrade.

, breaking ties arbitrarily. This is similar to the way

many airlines manage upgrades to the business class on their flights.

When a business-class seat becomes available it is given to the most

important customer waiting on an upgrade.

A very common queueing discipline is the LIFO (last-in-first-out)

discipline. In a LIFO Queue, the most recently added element is

the next one removed. This is best visualized in terms of a stack of

plates; plates are placed on the top of the stack and also removed from

the top of the stack. This structure is so common that it gets its own

name:

![]() . Often, when discussing a

. Often, when discussing a

![]() , the names of

, the names of

![]() and

and

![]() are changed to

are changed to

![]() and

and

![]() ; this is to avoid

confusing the LIFO and FIFO queueing disciplines.

; this is to avoid

confusing the LIFO and FIFO queueing disciplines.

A

![]() is a generalization of both the FIFO

is a generalization of both the FIFO

![]() and LIFO

and LIFO

![]() (

(

![]() ). A

). A

![]() represents a sequence of elements, with a front

and a back. Elements can be added at the front of the sequence or

the back of the sequence. The names of the operations on a

represents a sequence of elements, with a front

and a back. Elements can be added at the front of the sequence or

the back of the sequence. The names of the operations on a

![]() are self-explanatory:

are self-explanatory:

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() . Notice that a

. Notice that a

![]() can be implemented using only

can be implemented using only

![]() and

and

![]() while a FIFO

while a FIFO

![]() can be implemented

using only

can be implemented

using only

![]() and

and

![]() .

.

This book will talk very little about the FIFO

![]() ,

,

![]() , or

, or

![]() interfaces. This is because these interfaces are subsumed by

the

interfaces. This is because these interfaces are subsumed by

the

![]() interface. A

interface. A

![]() represents a sequence,

represents a sequence,

![]() , of values. The

, of values. The

![]() interface includes

the following operations:

interface includes

the following operations:

Although we will normally not discuss the

![]() ,

,

![]() and FIFO

and FIFO

![]() interfaces very often in subsequent chapters, the terms

interfaces very often in subsequent chapters, the terms

![]() and

and

![]() are sometimes used in the names of data structures that

implement the

are sometimes used in the names of data structures that

implement the

![]() interface. When this happens, it is to highlight

the fact that these data structures can be used to implement the

interface. When this happens, it is to highlight

the fact that these data structures can be used to implement the

![]() or

or

![]() interface very efficiently. For example, the

interface very efficiently. For example, the

![]() class is an implementation of the

class is an implementation of the

![]() interface that can implement

the

interface that can implement

the

![]() operations in constant (amortized) time per operation.

operations in constant (amortized) time per operation.

The

![]() interface represents an unordered set of elements. This

is a set in the mathematical sense. A

interface represents an unordered set of elements. This

is a set in the mathematical sense. A

![]() contains

contains

![]() distinct elements; no element appears more than once; the elements

are in no specific order. A

distinct elements; no element appears more than once; the elements

are in no specific order. A

![]() supports the following operations:

supports the following operations:

These definitions are a bit fussy about distinguishing

![]() , the element

we are removing or finding, from

, the element

we are removing or finding, from

![]() , the element we remove or find.

This is because

, the element we remove or find.

This is because

![]() and

and

![]() might actually be distinct objects that

are nevertheless treated as equal.

This is a very useful distinction since it allows for the creation of

dictionaries or maps that map keys onto values. This is

done by creating a compound object called a

might actually be distinct objects that

are nevertheless treated as equal.

This is a very useful distinction since it allows for the creation of

dictionaries or maps that map keys onto values. This is

done by creating a compound object called a

![]() that contains a

key and a value. Two

that contains a

key and a value. Two

![]() s are treated as equal if their

keys are equal. By storing

s are treated as equal if their

keys are equal. By storing

![]() s in a

s in a

![]() , we can find the value

associated with any key

, we can find the value

associated with any key

![]() by creating a

by creating a

![]() ,

,

![]() , with key

, with key

![]() and using the

and using the

![]() method.

method.

The

![]() interface represents a sorted set of elements. An

interface represents a sorted set of elements. An

![]() stores elements from some total order, so that any two elements

stores elements from some total order, so that any two elements

![]() and

and

![]() can be compared. In code examples, this will be done with a

method called

can be compared. In code examples, this will be done with a

method called

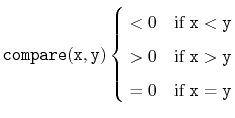

![]() in which

in which

This version of the

![]() operation is sometimes referred to

as a successor search. It differs in a fundamental way from

operation is sometimes referred to

as a successor search. It differs in a fundamental way from

![]() since it returns a meaningful result even when there is

no element in the set that is equal to

since it returns a meaningful result even when there is

no element in the set that is equal to

![]() .

.

The distinction between the

![]() and

and

![]()

![]() operations is very

important and is very often missed. The extra functionality provided by

an

operations is very

important and is very often missed. The extra functionality provided by

an

![]() usually comes with a price that includes both a larger running

time and a higher implementation complexity. For example, the

usually comes with a price that includes both a larger running

time and a higher implementation complexity. For example, the

![]() implementations discussed in this book all have

implementations discussed in this book all have

![]() operations

with running times that are at least logarithmic in the size of the set.

On the other hand, the implementation of a

operations

with running times that are at least logarithmic in the size of the set.

On the other hand, the implementation of a

![]() as a

as a

![]() in Chapter 5 has a

in Chapter 5 has a

![]() operation that runs in constant

expected time. When choosing which of these structures to use, one should

always use a

operation that runs in constant

expected time. When choosing which of these structures to use, one should

always use a

![]() unless the extra functionality offered by an

unless the extra functionality offered by an

![]() is really needed.

is really needed.

opendatastructures.org