Next: 6. Binary Trees Up: 5. Hash Tables Previous: 5.3 Hash Codes Contents

Hash tables and hash codes are an enormous and active area of research that is just touched upon in this chapter. The online Bibliography on Hashing [7] contains nearly 2000 entries.

A variety of different hash table implementations exist. The one described in is known as hashing with chaining (each array entry contains a chain (List) of elements). Hashing with chaining dates back to an internal IBM memorandum authored by H. P. Luhn and dated January 1953. This memorandum also seems to be one of the earliest references to linked lists.

An alternative to hashing with chaining is that used by open addressing schemes, where all data is stored directly in an array. These schemes include the LinearHashTable structure of . This idea was also proposed, independently, by a group at IBM in the 1950s. Open addressing schemes must deal with the problem of collision resolution: the case where two values hash to the same array location. Different strategies exist for collision resolution and these provide different performance guarantees and often require more sophisticated hash functions than the ones described here.

Yet another category of hash table implementations are the so-called

perfect hashing methods. These are methods in which

![]() operations take

operations take ![]() time in the worst-case. For static data sets,

this can be accomplished by finding perfect hash functions for

the data; these are functions that map each piece of data to a unique

array location. For data that changes over time, perfect hashing

methods include FKS two-level hash tables [25,19]

and cuckoo hashing [48].

time in the worst-case. For static data sets,

this can be accomplished by finding perfect hash functions for

the data; these are functions that map each piece of data to a unique

array location. For data that changes over time, perfect hashing

methods include FKS two-level hash tables [25,19]

and cuckoo hashing [48].

The hash functions presented in this chapter are probably among the most

practical currently known methods that can be proven to work well for any

set of data. Other provably good methods date back to the pioneering work

of Carter and Wegman who introduced the notion of universal hashing

and described several hash functions for different scenarios [11].

Tabulation hashing, described in , is due to Carter

and Wegman [11], but its analysis, when applied to linear probing

(and several other hash table schemes) is due to P![]() tra

tra![]() cu and

Thorup [53].

cu and

Thorup [53].

The idea of multiplicative hashing is very old and seems to be

part of the hashing folklore [41, Section 6.4]. However, the

idea of choosing the multiplier

![]() to be a random odd number,

and the analysis in is due to Dietzfelbinger et al. [18]. This version of multiplicative hashing is one of the

simplest, but its collision probability of

to be a random odd number,

and the analysis in is due to Dietzfelbinger et al. [18]. This version of multiplicative hashing is one of the

simplest, but its collision probability of

![]() is a factor of 2

larger than what one could expect with a random function from

is a factor of 2

larger than what one could expect with a random function from

![]() . The multiply-add hashing method uses the function

. The multiply-add hashing method uses the function

There are a number of methods of obtaining hash codes from fixed-length

sequences of

![]() -bit integers. One particularly fast method

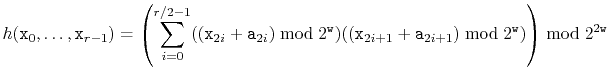

[8] is the function

-bit integers. One particularly fast method

[8] is the function

The method from of using polynomials over prime fields

to hash variable-length arrays and strings is due to Dietzfelbinger et al. [17]. It is, unfortunately, not very fast. This is due to its

use of the ![]() operator which relies on a costly machine instruction.

Some variants of this method choose the prime

operator which relies on a costly machine instruction.

Some variants of this method choose the prime

![]() to be one of the form

to be one of the form

![]() , in which case the

, in which case the ![]() operator can be replaced with

addition (

operator can be replaced with

addition (

![]() ) and bitwise-and (

) and bitwise-and (

![]() ) operations [40, Section 3.6].

Another option is to apply one of the fast methods for fixed-length

strings to blocks of length

) operations [40, Section 3.6].

Another option is to apply one of the fast methods for fixed-length

strings to blocks of length ![]() for some constant

for some constant ![]() and then apply

the prime field method to the resulting sequence of

and then apply

the prime field method to the resulting sequence of

![]() hash codes.

hash codes.

boolean addSlow(T x) {

if (2*(q+1) > t.length) resize(); // max 50% occupancy

int i = hash(x);

while (t[i] != null) {

if (t[i] != del && x.equals(t[i])) return false;

i = (i == t.length-1) ? 0 : i + 1; // increment i (mod t.length)

}

t[i] = x;

n++; q++;

return true;

}